SystemSpecs: A Transgenerational (Fin)tech Company

The 31-year old quiet tech behemoth that powers the Nigerian government’s treasury and hundreds of organisations across Africa.

Hi there,

I was midway through writing a piece on the early days in the Nigerian fintech space when I zoomed in on one of the players and got intrigued.

So now I have a half-written abandoned article lying somewhere – that I'll finish sometime in the future – and this completed one you’re about to read.

There’s a recurring conversation that comes up now and then on how Nigeria has very few transgenerational companies, largely due to poor succession planning, unsustainable business models and the declining economy.

With very few companies making it past the five-year mark, there are a few outliers in Nigeria — mostly traditional companies. So I dug deep into the story of this 31-year-old company, to see if I had a few answers on what it takes to be a transgenerational tech company in Nigeria.

🥸Let’s dive in.

If you’re familiar with the Nigerian fintech space you’ve probably heard of SystemSpecs or its most popular product Remita — an electronic payment platform that processes trillions of Naira every month.

The software products of this quiet tech behemoth power the Nigerian federal government’s treasury and hundreds of organisations across Africa.

How has it remained alive for over 3 decades?

SystemSpecs’s origin story dates back back 50 years, to its CEO, John Obaro’s time as a secondary school student of Baptist College Ilorin. Born in Kogi state, he spent his formative years living between the cities of Kano and Ilorin in northern Nigeria.

Obaro, like many of his classmates, wasn't interested in maths. The subject was so unpopular that a student once submitted an exam answer sheet that contained only an image of his traced palm – he didn’t attempt any questions.

But a turning point came when a new maths teacher Raphael Awoseyin, who later went on to be the chief engineering and technology officer at Shell Nigeria, came with a different teaching style that sparked Obaro’s interest in the subject.

Obaro’s newfound love for maths led him to study Mathematics and Computer Science at the Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) in Zaria, Kaduna and graduating in 1979. For a computer science graduate back then, most of the good job opportunities were situated in Lagos but Obaro wasn’t keen on moving to Lagos. His next move was to get an MBA.

“I decided that if I was going to stay in the North, I needed to empower myself to be able to take on a non-computer job. So naturally, doing an MBA came up. But then again, the best place to do an MBA at the time was the University of Lagos (Unilag).” Obaro said.

His parents, especially his mum, were apprehensive about him going to Lagos because they had heard that people got robbed and drowned in the sea. After much back and forth, both parties settled on Obaro going for his MBA in Lagos but with the promise that he’ll return to the North to get a job.

After his MBA, Obaro remained in Lagos working briefly at the Leventis group, before working at two financial institutions for the next decade. He spent two years as a software developer at the United Bank for Africa (UBA) and then rose to the rank of the Head of IT Department at the now-defunct International Merchant Bank (IMB).

Obaro knew it was time to move on to his next adventure after successfully implementing a major project at IMB – installing banking software across four major cities in Nigeria. He was considering going for further studies but some friends advised him to start a business instead.

One of them, Gbade Alabi, who supplied computer systems to IMB, told the rather uninterested Obaro that while he was a computer manager if he made the move to start a business, he’d be able to control computer managers across different organisations.

By this time Obaro was married with kids, so he had to be prudent. A year before he left his job, Obaro relocated from his expensive rented house in Victoria Island to his property in Agbara, Ogun state. This increased his work commute from 5 minutes to 3 hours but delivered the cost savings he required as he prepared to resign from one of the highest-paying organisations in Nigeria to venture into the land of the unknown.

“So many people thought I had lost my mind,” Obaro said in an Interview during its 30th anniversary. “But I guess I was too ignorant or maybe desperate to do something new, so I still left with limited funds and counted on God’s favour.”

Image: SystemSpecs Logo at its office

How to Make a Million Naira in 1992

In January 1992, 33-year-old Obaro founded SystemSpecs, to provide financial software for companies. He saw an opportunity to provide software to industries that were manually operated. At that time, the banking and oil industries were the only industries run by software.

Rather than building one from scratch, SystemSpecs began by partnering with a UK-based business management software firm called Systems Union (acquired by Infor in 2007) to be their official sales representative in Nigeria. Over the next 25 years, SystemSpecs will go on to sell SunSystems’ suite of solutions — financial management solutions with purchasing, inventory and sales management capability — to many African companies.

Even with this partnership in place, Obaro’s initial business plan needed a million Naira ($100,000)1 to cover the company’s running costs for a year. Raising a million Naira proved difficult as initial efforts to get a bank loan fell flat. A few friends had contributed some seed funding but it still wasn’t enough.

Amid the failed efforts to raise funds, a bright idea made it rain.

Obaro had earlier attended a training programme, at Cranfield University in the UK, so he partnered with the organisers to bring the training to Nigeria. For the training, they charged ₦50,000 ($5,000), an unusually high amount, considering that most professional courses in those days were typically priced at ₦3,500 ($350). Fortunately, 19 people were interested, helping them generate ₦950,000 ($95,000).

The team struck gold when those 19 people who found the training valuable requested that Obaro and his team repeat it. They referred another 16 who came in for the second batch.

All this happened within the first three months of the new company’s existence. With SystemSpecs’ money issues sorted, it now had to prove that its business model worked, by doing what it set out to do: sell computer software.

Dealing with market ignorance

“Selling software in those days, especially in Nigeria was not something that happened instantly,” Obaro said in another interview. “The sales cycle, if you were lucky, was about 3 to 6 months. Otherwise, you would be looking at 1 to 2 years, revisiting the same potential clients to educate them on the benefits of computers.”

Obaro was trying to sell software at a time when people barely knew the difference between Hardware and Software. The depth of ignorance in the market can be best depicted by two absurd events.

In the late 90s, a SystemSpecs staff travelled by road for 6 hours from Lagos to Ilorin to deliver a software project, only for the client to refuse the small box that contained a CD and manual.

“The client said what they paid for was more than that. The staff had to return to Lagos with the box,” Obaro said. It took weeks of conversations to convince the client that what they got was what they ordered.

Image: John Obaro

Another incident took place in the early 2000s when a government agency was being investigated for fraud and the investigating agency found a ₦10 million ($88,495) payment made to SystemSpecs for Software.

The large amount raised suspicions, so SystemSpecs was contacted to show the investigators where the software product earlier delivered was. Recurring explanations that software isn’t something that can be touched, fell on deaf ears.

“Initially, you’ll think this was a joke but the staff who was in charge of the project was locked up for three days because the investigating agency didn’t see the software,” Obaro said.

Over time, the Nigerian market became more familiar with the importance of computer software as digital literacy increased.

It's Time to Build

Three years into reselling foreign software, Obaro and his team decided it was time to build their software to solve problems for Nigerian organisations.

A glaring opportunity arose in the payroll software space as most foreign payroll systems didn’t reflect the peculiarities of local employment, remuneration and taxation environment. So the team built SpecMan for human resource management, SpecPen for managing pensions and Spec Pay focused on Payments. These three products were later merged to form Human Manager, a comprehensive payroll solution in 2000. Human Manager went on to gain wide adoption processing payroll for more than 300 companies across Africa including KPMG, British Airways, and The Palladium Group. At its peak in the early 2000s, about 80% of the banks in Nigeria were running on it.

SystemSpecs rose to further limelight in Nigeria through its implementation of a World Bank-backed project to implement an integrated payroll solution.

On May 6, 2006, the Nigerian government announced a public service reform program that involved creating a reliable and comprehensive database for the public service to address ghost workers syndrome, facilitate human resource planning, and eliminate manual record and payroll fraud.

Out of fifteen companies from across the globe that bidded to carry out the pilot phase of the project that entailed 10 MDAs, SystemSpecs won. In October 2006, SystemSpecs successfully ran the IPPIS pilot, processing salaries for 50,000 employees of the federal government. The project saved Nigeria ₦450 million ($3.4 million) according to former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo in his book My Presidential Legacy.

After the successful pilot, there was some pushback from the other companies which bid for the project, citing the existence of foul play. How could a local Nigerian firm upstage well-known international brands?

Petitions were sent to the World Bank, which responded by carrying out an investigation. Over two weeks, four investigators from Washington combed through a plethora of invoices, bank statements, and receipts at SystemSpecs’ office in Abuja. At the end of the investigation, SystemSpecs was cleared.

The success of the IPPIS pilot came with mixed results. While it validated the capabilities of Human Manager, it also woke competitors who intensified their efforts to ensure that when the full-scale rollout was done in 2011, a different vendor was used.

Human Manager has kept evolving over the years; moving to being a cloud-based service in 2012 and expanding to Ghana in 2018.

Laying the foundation for Remita

Sometime in 2004, the Human Manager team decided to add a feature that would enable users to disburse payments from the application. They initially looked around for an existing payment solution to integrate but they decided to build one in-house when none suitable was found.

In 2005, Remita was born as a solution to help pay salaries in organisations, deliver tax schedules across states, and pensions. The name Remita was a no-brainer considering that the purpose of the feature was to Remit payments.

Later, it spawned as a stand-alone product that could be used by other companies for payments. Other features such as the ability to pay bills, view different bank accounts from one interface and manage multiple profiles were also added.

By 2007 an opportunity presented itself for Remita to be used by the government for the Petroleum Equalisation Fund (PEF), a body tasked with ensuring the uniformity of petroleum products prices across the country by reimbursing oil marketers when they incur extra costs in transporting petroleum products from depots to their sales outlets.

The successful deployment of Remita meant that about 2,000 cheques signed daily to oil tanker drivers were replaced with electronic payments, cutting down the massive fraud going on.

Shortly after, Nigerian President Umaru Musa Yar'Adua got wind of the success of the PEF and he directed that all FG payments must be made electronically. This sowed the seed for initiating the Treasury single account (TSA), a process and tool that consolidates all government accounts in a single unit for the effective management of its finances, bank and cash position.

You don't lose anything by letting CBN know what you are doing

With the directive, the Ministry of Finance and CBN had to find the right payment solution to make electronic payments and the TSA work.

Initially, the CBN had planned to delay the implementation of the TSA project by two years to build a financial platform. But during one of the apex financial regulator’s routine visits to SystemSpecs’ office in 2011, they asked about Remita and upon further discussion found out that it could be used to facilitate the payment of government revenue from financial institutions to the TSA. A couple of solutions including the Nigerian Inter-Bank Settlement System (NIBSS), which is owned by the CBN and commercial banks were considered as an option but eventually, after competitive bids, Remita was selected.

In January 2012, the federal government started using Remita for payments of salaries and contractors. Three years later, following the directive of President Muhammadu Buhari in August 2015, over 20,000 bank accounts run by federal ministries and 600 government agencies were closed and merged into a single view for the government.

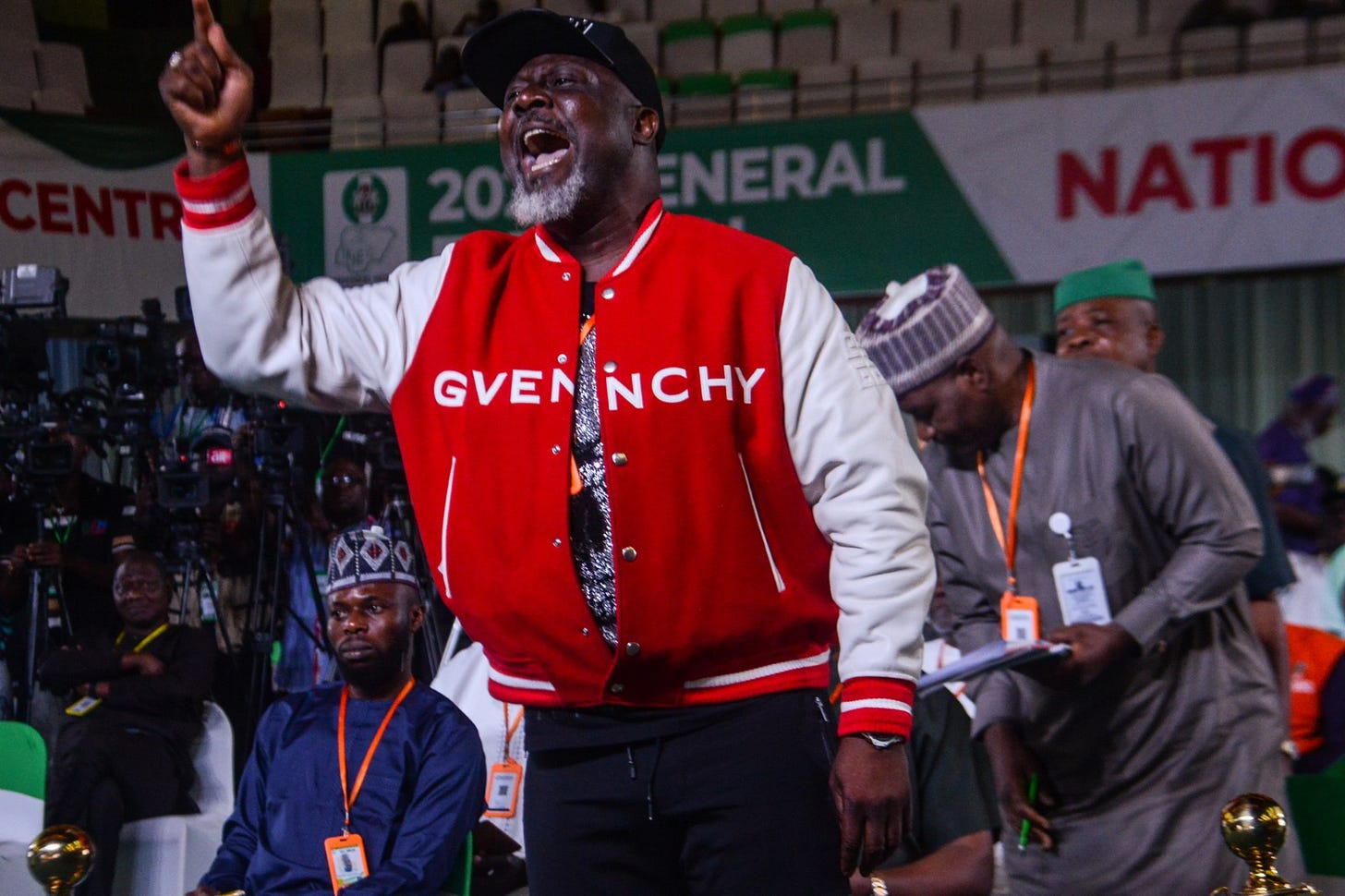

Image: Senator Dino Melaye

On Tuesday, 10 November 2015, Dino Melaye, a Nigerian senator raised a motion that the operation of the treasury single account (TSA) be investigated for possible corruption. He claimed the constitution only recognised a banking institution to be the collector of government funds, and that Remita was not a bank. This outcry necessitated SystemSpecs to return ₦8.6 billion earned commission fees to the CBN pending the outcome of an investigation. At the end of the investigation, the claim was debunked as Remita was only a payment processing platform through which the payments were made to the banks.

The ordeal revealed that a 1% commission was charged on the ₦2.5 trillion ($12.5 million) processed by SystemSpecs between April and September. This commission was shared between SystemSpecs, participating commercial banks and the Central Bank of Nigeria in the ratio of 50:40:10 respectively. The commission structure was afterwards reviewed from 1% to ₦150 for payments made through Internet Banking, Mobile Wallets, and Agents.

In July 2019, a representative of Nigeria’s Accountant-General of the Federation (AGF) shared that since its inception the government had collected over ₦10 trillion through the TSA from 1,674 MDAs and saved over ₦45 billion monthly in interest on borrowed loans from banks and the CBN.

Looking back at the past decade, Obaro has described the years of handling the TSA project with mixed feelings. The deal might have made Remita more popular but it has also been attention-sapping and has given the public a perception that it is a product owned by the government despite its diverse customer base.

“Sometimes we’re excited we got the [TSA] project, other times we believe it has distracted us from doing other things,” he said. “But through it all, we give glory to God.”

Reseller → Group of companies

SystemSpecs has come a long way from a reseller of foreign software to a holding company with over 300 staff.

Although it’s a private company and its numbers are not disclosed, Emmanuel Ocholi, an early investor gave a glimpse of how well the company faired during the company’s 30th anniversary when he shared that within two years of investing in the company, he had made a ten-fold return.

At the same 30th anniversary event, the company announced it was morphing into a holding company structure with SystemSpecs being a holding company while Remita, Human Manager, Deelaa and SystemSpecs Technology Services Limited as subsidiaries. Deelaa, a ticketing platform, is the latest addition to the SystemSpecs group of products.

The evolution of SystemSpecs could not have been predicted when Obaro started, but by paying attention to the tenets of business2 — solving real-world problems, fostering a culture of innovation and building a sustainable business model — he has built a transgenerational company.

Thanks to Victor for editing!

Exchange rate of 1 Dollar to Naira:

1992: ₦10

2002: ₦113

2006: ₦131

2015: ₦200

Plus a sprinkle of luck/favour.