eTranzact: The most valuable Nigerian publicly listed fintech company

20 years of innovation, battling losses and tremendous growth

Hi there,

What was it like building a fintech company before it became popular? And what do the numbers of a company say about its performance and DNA? That’s a question I’ve had for a while. So I turned to a company that I relied on to pay my school fees at University.

Now playing behind the scenes, eTranzact is one of Nigeria’s most important fintech companies which pioneered mobile banking, USSD, and cardless withdrawal. It provided interbank switch service before NIBSS became functional. A recent resurgence of its stock price has also made it the most valuable Nigerian publicly listed fintech company1 at a valuation of ₦77 billion ($77 million).

🤓Let’s dive in.

Ps: I’ll be in your inbox every 2 weeks, on Friday mornings. 🙏🏾

The world was so much different back then. It was the dawn of the new millennium.

With the memory of the 9/11 attack still fresh, it was the year the US invaded Iraq. Swiss tennis player Roger Federer won his first Grand Slam title at Wimbledon. Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, the final instalment in the movie trilogy, surpassed Finding Nemo and Matrix Reloaded to clinch the top spot as the highest-grossing film that year. Get Rich or Die Tryin' by American rapper 50 Cent dominated the airwaves and ended up being the best-selling album globally with 12 million copies.

The world was still recovering from the early 2000s dot-com stock market crash but a string of recent failed tech companies wasn’t enough to stop American electric car company Tesla from being founded in July and social networking service Myspace in August of that year.

To bring things close to home, new elections were organised for the first time in 15 years in Nigeria by a civilian government. The incumbent government won by a landslide.

The year was 2003. The liberalisation of the Nigerian telecommunications sector introduced telephone connectivity and mobile phones to many Nigerians for the first time. In two years, the number of telephone connections added surpassed the 400,000 lines that served the whole country as of 2000. For context, connected lines grew at an average growth rate of one million lines per annum between 2001 and 2002, compared to an average growth of 10,000 new lines per annum in the four decades between Nigeria’s independence in 1960 and the end of 2000. Internet penetration was also inching forward, moving from 0.1% in 2000 to 0.3% in 2002. By the end of 2003, there were only about 750,000 internet users in a country of 133 million people.

Paying for transactions with cash was the order of the day. Despite less than 7% of Nigeria’s population having a bank account, this translated to long queues at banks as people visited to sometimes know their account balance.

The rapid growth of telephone connectivity coupled with inefficiencies in the Nigerian financial service sector stirred up fire in the belly of 38-year-old Valentine Obi. “I was very concerned by the high circulation of cash. If you had to buy a house or car, you had to carry a load of cash to make payment,” Obi said in an interview.

So he decided to dip his toes into the uncharted waters of entrepreneurship by starting a new company, eTranzact, to facilitate financial transactions in a convenient, secure and cost-effective manner. Some of the earliest customers of the new venture were telecom giant Econet Wireless (now Airtel) and Lagos State Water Corporation.

Getting a few customers didn’t absolve the new company from facing many huddles as the idea of facilitating payment via mobile phone was a strange concept for Nigerian consumers and regulators.

“In 2003, it was a non-starter. People were still struggling to learn how to use their phones to make calls and send SMS. How do you layer payments on that?” Obi said.

Sometime in 2003, Obi met with the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) concerning his plans. After a lengthy enthusiastic explanation of his plans to make transactions cashless in the country, the director smiled and politely walked him out of his office asking him to share periodic updates on how things were going. It’ll take almost a decade, according to Obi, before the apex monetary regulator and the Nigerian banking sector will take the concept of mobile banking seriously.

Trust issues and wonky infrastructure

Within the next decade, the bootstrapped company expanded its operations amid many struggles. The company started integrating with many banks and the major telcos in Nigeria. Its first product was mobile-based and reliant on SMS (text messaging) with airtime top-up being a popular use case. However, the success of the SMS-powered service was hampered by the effectiveness of the telcos which often experienced delays in delivering messages. During one of its product demonstrations with the CBN, a transaction was performed using SMS to the officials present but disappointingly no one got the SMS notification until the next day.

“If you are making a payment to the average person out there, he wants to take that money or give you that money while he is looking you in the eye so there will be no stories," an executive of the company said. “For instance, if I did a transfer and told you I have done it, you can tell me you did not receive it or I tell you it’s done even though I didn’t do it.”

Inefficiencies like this coupled with Nigerians' trust issues with digital payments only made it more difficult for mobile payment to gain mass adoption.

Over time, seeing the rise in mobile phone and internet penetration, the engineering team at eTranzact suggested turning to mobile phone applications which rely on internet data as a better alternative.

This proved to be a worthwhile endeavour as the company did the leg work of integrating into most banks in the country with a switching service for facilitating payments. Here’s how a switching service works: when you initiate a payment, the payment switch coordinates the movement of funds from your bank account to the recipient's account. It ensures that the right information is transmitted securely, authorises the transaction, and verifies that the funds are available.

Back then there wasn’t a central inter-bank settlement service so eTranzact had to step in. Life was made easier in 2005 when the Nigerian banking sector experienced a shake-up which saw the number of banks pruned down from 89 to 25 through mergers and acquisitions. This enabled eTranzact’s services to be used for funds transfer, point of sale terminals, automated teller machines, and revenue collection for state governments and other organisations.

The rise in electronic payments led to fraudsters taking advantage of this new mode of payment. To protect users from fraud, the company launched Etranzact strong Authentication (ESA) to protect customers' pins, automated teller machine cards and banks' online transactions. ESA was simply a second-factor authentication service separate from card PIN that provided a one-time passcode for transactions.

Another product introduced to mitigate against fraud was the ATM CardlexCash solution, which the company patented. Here’s how it worked as explained by Obi in 2010:

“I key in the amount I want to send to the recipient on my mobile phone and an access code which he will use to withdraw the fund. Then, I inform the recipient of the access code via other means. The recipient will cash out the exact funds at the ATM using the access code.

This innovation proposes a secure, faster and more convenient process of sending money and cash withdrawals at the ATM. With this solution, the recipient does not need to have a bank account to receive funds and does not need to go to a bank branch to collect funds, which can only be done during working hours. It also eliminates the need to use an ATM card to withdraw money.”

This solution introduced cardless withdrawals in Nigeria.

Going public

On Wednesday, July 8, 2009, eTranzact took its next big step by going public. The company was listed on the Nigerian stock exchange at ₦4.80, selling about 720,000 shares out of the 4.2 billion shares listed. The market’s positive response caused the share price to surge, closing at ₦5.04 and bringing its market cap to ₦21.16 billion ($14.39 million)2 on the first day.

At the listing ceremony, Obi preached the same message he did in 2003.

“Nigeria presently has over 60 million mobile telephone users and less than 20 million of the populace with bank accounts…”, he said. “The market potential is huge and we hope to reduce the risk involved when people conduct transactions with cash. With the current trend and manner in which fraudsters are perpetrating their acts, it has become a necessity to discourage cash transactions."

The company shared that it was in talks with the Nigerian stock exchange to enable Nigerians to buy and sell shares digitally, through an electronic offering service. It’s not clear whether this idea moved beyond the talking and testing stage.

Getting listed offered eTranzact the lifeline it needed to stay alive as the company struggled to be profitable in the following two years, making combined losses of over ₦300 million ($2 million) – ₦174.69 million ($1.16m) in 2009 and ₦134.69 million ($874,600) 2010.

Fortunes turned around in the third year (2011) when the company made a profit of ₦81.29 million ($53,480). This was largely driven by a 145% increase in revenue from ₦917 million ($6.03 million) in 2010 to ₦2.24 billion ($14.7 million). As most banks caught on to the importance of mobile apps, eTranzact was their go-to partner for the creation and maintenance of their apps.

Coincidentally, 2011 was also the year investment banker and chartered accountant Niyi Toluwalope joined the company as its group CFO. The road to profitability was paved by shutting down products that weren’t selling and doubling down on the ones which were.

“Joining E-Tranzact in the early stages, we struggled a bit with profitability. This was largely because we were doing so many products, being a very innovative business. I felt that we were not optimising our ability to sell them properly and dominate the market,” Toluwalope said in an interview. “One of the things we did quickly was to streamline our products and look at what was profitable and what wasn’t. We focused on that and things started to change. Our remittance business, mobile banking business, corporate banking business everything transformed into profitability over the last couple of years.”

The CBN’s aggressive pursuit of a cashless economy propelled it to grant eTranzact its final approval to operate a mobile money business. Pocket Moni, the company’s mobile money app, was launched to reach one million users within the next year.

Around 2012, the company also laid the foundation for the popular Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) service used in Nigeria. Taking inspiration from Steve Jobs who created the iPod as a minimalistic and improved version of the Walkman, the team asked themselves why they couldn’t make payments happen with a few clicks on the phone.

Once eTranzact became profitable there was no turning back, its revenue, largely driven by transaction pin sales/virtual airtime, grew by leaps and bounds every year for the next decade. For ease of understanding, eTransact makes money by taking a commission from facilitating transactions.

Back then it was also a regular practice for merchants who wanted to use its payment solution to be charged a ₦150,000 ($77) implementation fee. Newer fintech startups like Paystack and Flutterwave differentiated themselves by offering free merchant onboarding and easy integration.

Regulatory Sanctions and a Massive Fraud Case

2016 was the first time eTranzact revealed its income from remittance; it made ₦1.12 billion ($5.71M) the previous year and ₦1.23 billion ($3.90M) in 2016. A 20% increase in revenue from ₦8.7 billion ($44.38M) to ₦10.4 billion ($33.01M), courtesy of a 190% increase in revenue from software development and maintenance, wasn’t enough to stop the company from experiencing a decline in profit.

Why? A ₦450 million ($1.42M) fine by the CBN for “infractions on International money transfer and anti-money laundering guidelines in 2014 and 2015.” This first-time sanction for the 13-year-old fintech giant, one largely suspected to be linked with its remittance business, came as a huge blow that made it cautious. The fall in profitability continued the next year, primarily due a to drastic drop in remittance income from ₦1.23 billion ($3.90M) in 2016 to ₦91.8 million ($25,714) in 2017.

2018 was meant to be the year that eTranzact returned to its regular trend of increasing profitability based on its 37% increase in revenue, which was largely driven by a 72% increase in mobile transactions. Yet the company experienced a loss of ₦3.4 billion ($9.34M) – its biggest loss in its history and its first loss since 2010 – against a ₦208 million ($57,142) profit in 2017.

What happened? A ₦11.49 billion ($31.5M) fraud case reported by First Bank in March 2018, involving Micro Systems Limited, a merchant on-boarded to the eTranzact Fundgate platform.

The fraud scheme was orchestrated by Smart Micro Systems Limited (SMSL). This merchant onboarded microfinance banks on eTranzact's Fundgate platform, a payment gateway used by financial institutions to process interbank transactions. SMSL allegedly exploited vulnerabilities in the Fundgate platform to initiate unauthorized transfers of funds from various banks. SMSL MD, Michael Obasuyi Osasogie pleaded guilty to defrauding the First Bank and eTranzact.

About half of the funds stolen were recovered but ultimately, eTranzact and First Bank were instructed by CBN to share the remaining liability of ₦5.75 ($15.79M) equally, meaning eTranzact had to cough up about ₦2.8 billion ($7.69M) to repay the money stolen.

In response to the fraud and the CBN's findings that eTranzact hadn’t implemented adequate security measures to prevent fraudulent activities, eTranzact's board of directors took several measures to address the situation. Several senior executives, including founder and CEO Obi, resigned. The company implemented stricter security measures to enhance its defences against future fraud attempts. Since this incident, there’s been no fraud incident at eTranzact.

Change of Guard and returning to profitability

Group CFO Niyi Toluwalope took over as CEO and began the turnaround process of the fintech company which was written off by many. In 2019, the company returned to being profitable with a profit of ₦147 million ($397,300).

2020 was a year for the books, for many companies across the globe and eTranzact wasn’t exempted. Due to the pandemic, its major revenue stream mobile sales (proceeds from virtual airtime and airpin sales) dropped for the first time ever and every other revenue stream followed suit. The company made a loss of ₦1.8 billion ($3.87M) primarily due to a ₦1.048 ($2.25M) billion provision related to assets recovered from the 2018 fraud case.

In 2021, the company was back to experiencing revenue growth, despite mobile sales continuing to fall. It also returned to being profitable with a massive ₦455.75 million ($799,500).

Earlier in the year eTranzact clinched major business contracts with the government. It was appointed to deploy its automated and electronic collection platform for the Federal Government’s Treasury Single Account (TSA) and payment gateway for the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA). Under the TSA scheme, eTranzact processes all revenues and other monies payable to Federal Government public sector entities including Ministries, Departments, Agencies, Parastatals and Institutions.

Curiously, there was no remittance income recognised compared to ₦348 million ($748,387) generated in 2020. Also, for the first time, the company broke down its revenue according to the licences it had. Switching licences was recognised as its biggest revenue driver.

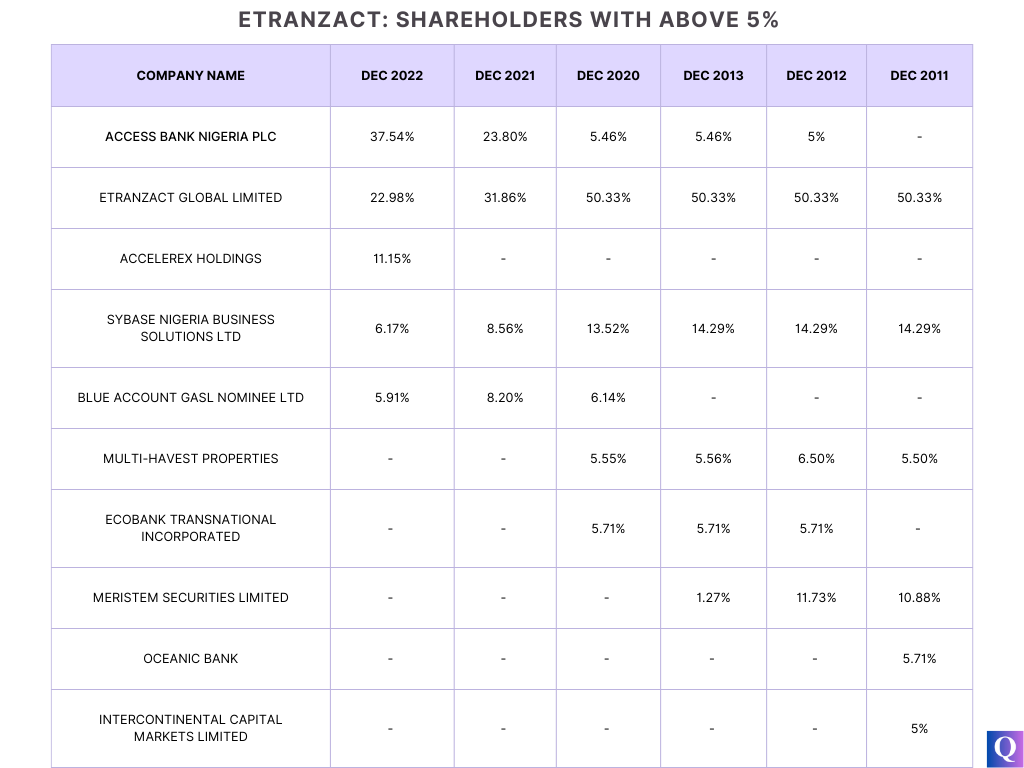

Nigeria’s largest retail bank, Access Bank, which had been a dormant shareholder for over a decade since it acquired eTranzact shares via its purchase of Intercontinental Bank, increased its shareholding to 23.80%, becoming the second largest shareholder. The bank further increased its shareholding to 37.54% in 2022 becoming the largest shareholder.

2022 was the eTranzact’s best year yet, it processed over ₦50 trillion ($6.25 billion) and generated a profit of ₦1.17 billion ($1.46M) – almost tripling its 2021 profit. It also raised ₦5.7 billion through a right issue of shares. This year, 2023, already looks better than last as the company has generated 77% of 2022’s total revenue by mid-year.

Different sides of the same coin

There are different ways to look at this 20-year-old fintech giant. It's impressive that it pioneered mobile payments in Nigeria and is still thriving. eTranzact alongside the likes of Interswitch, Unified Payments and others spent their first decade building out the supporting infrastructure for Nigerian financial services and lobbying to get regulation to come along.

It had a first-mover advantage, which definitely provided advantages in many cases. But as American psychologist Adam Grant is credited with saying, “While it’s true that the early bird gets the worm, the early worm also gets caught.” For eTranzact, was it a case of the early bird or worm? I’ll say that surviving 20 years makes it the early bird.

Battling to stay alive, being regulated as a publicly listed company and facing sanctions have shaped the DNA of the eTranzact. It has had to prioritise being financially responsible (as evident in its low debt profile) and cautious with its business dealings — staying far away from the crypto wave.

On the other side, eTranzact also represents the old guard and with the current wave of highly valued startups, its ₦77 billion ($77 million) market cap might not come off as being impressive – even though it’s debatable what’s the true valuation of the current wave of fintech startups. Also, the ₦77 billion looks small when converted to USD largely due to the appalling devaluation of the Naira over the years – in 2009, $1/₦147; today $1/₦1,000.

Some finance industry insiders I interviewed for this article questioned the relevance of eTranzact’s business offerings, raising questions such as “Who will the banks switch to when there are issues?” (Interswitch appears to be more popular) and “Do the new fintech startups do business with eTranzact?” eTranzact’s primary clients are banks and the government for now, not fintech startups.

eTranzact’s moat comprises of its licences (switching especially), deep integration with the banks and multiple product lines – too many initially – that help diversify its revenue streams. Its product lines include:

Payoutlet: a solution designed to allow Merchants to collect payments from customers through the branches of eTranzact member bank. Individuals can also use it to pay bills, send money and top-up mobile phones.

SwitchIt: A payment switch.

WebConnect: A payment gateway.

CorporatePay: A platform for bulk enterprise payments.

Bankit: Launched in 2016, it's a secured omnichannel direct-to-bank payment gateway enabling consumers to complete payments from their bank account.

With more players getting these licences and building out their interbank integration systems3, it’s only a matter of time before its clients become competitors. Notably, in terms of debit card schemes eTranzact isn’t a principal partner to Visa or Mastercard like Interswitch and Unified Payments. The highly prized position allows them to offer a range of payment products and services, including credit cards, debit cards, and prepaid cards — cards that are widely accepted both nationally and internationally.

It’s common knowledge that in Nigeria one change in government regulation can wipe out a revenue stream or even an entire business. Fortunately, eTranzact has been able to navigate through that despite its not-so-pronounced international expansion. From the get-go eTranzact set out to serve more countries beyond Nigeria but in terms of international operations, Ghana is the only visible foreign market that the company has a presence in.

It was a smart move to capture the market early but it’s plausible to imagine that eTranzact faced similar or worse huddles in those markets and retreated. Interswitch appears to have performed better in that regard. Is it time to reconsider an international play?

eTranzact has maintained its focus on facilitating digital payments and still has a long way to go. Coming from a different era and making it this far is laudable. But what’s next? A social commerce product in beta phase and the relaunch of Pocketmoni app in view, make me wonder if these are hints of its next evolution.

The world is so much different now but there are still queues at the bank and cash is still king despite many players in the fintech space. There’s still work to be done and as one company insider repeatedly told me as I questioned eTranzact’s position in the market, “One player cannot serve the entire market.”

There are about seven IT or tech companies listed on the Nigerian stock exchange. Out of the six, four of them have some element of fintech but eTranzact is the only pure play fintech company. The other count as fintech because they offer some form of service or product. CWG offers payment terminal solutions, Chams offers a payment switch service while NCR sells and maintains ATM machines.

Exchange rate of $1 Dollar to Naira:

2009: ₦147

2010: ₦150

2011: ₦152

2012: ₦153

2013: ₦156

2014: ₦179

2015: ₦196

2016: ₦315

2017: ₦357

2018: ₦364

2019: ₦370

2020: ₦465

2021: ₦570

2022: ₦800

2023: ₦1,000

Nigerian Banks are forming their own payment providers: Access Bank (Hydrogen), UBA (Redtech), GTB (Squad), and Stanbic (Zest).

This is very insightful. Well done!