The unseen power of being number Two | Adia Sowho

Renowned tech leader and the former CMO of MTN Nigeria, Adia Sowho, on why the smartest strategy isn't always about being first

Hey there,

It’s been a minute. After a brief stint to take the helm at Condia, I’m thrilled to be back in the editor’s chair here at Quest. It feels like returning to a conversation with old friends. And what a conversation we have to mark our return, learning from one of the brightest minds in the world. This newsletter edition is an excerpt from a podcast conversation I had.

Let’s dive in.

We’re taught to chase the top spot. The gold medal. The market leader. In the startup world, it’s about becoming the “category king,” the undisputed number one. We lionise the trailblazers, the first movers, the ones who plant the flag.

But what if this obsession with being first is a trap?

What if the real power, the smarter strategic position, lies in second place?

This is the provocative, counterintuitive idea at the heart of my recent conversation with Adia Soho, a venture builder and operator whose career reads like a masterclass in African tech. As the first-ever female CMO at MTN Nigeria and a leader who has scaled ventures from the seed stage to public listing, Adia has seen the game from every angle. And from her vantage point, being number two isn’t a consolation prize; it’s a strategic choice.

“If you’re the person that’s like, ‘Oh, I see something to optimise, I don’t have as much cash, I don’t have the resources for market validation,’ then go ahead and be number two,” she told me. “But be a very good number two.”

That single idea stopped me in my tracks. It reframes the entire narrative of competition, shifting it from a brute-force race to a calculated game of chess.

On being a fast follower

The allure of being number one is obvious: you set the standard, shape the market, and own the narrative. But the costs are equally massive. The market leader bears the burden of educating customers, spending enormous sums on marketing to create a new category and validate a new behaviour. They absorb the arrows, test the unproven tech, and iron out the kinks.

The number two, Adia argues, gets to play a different game.

She recalled her time at a US telco that was perfectly content being a top-ten player, not number one. Their strategy was simple: “Let Verizon go and test it. When they’re finished, we’ll buy the improved version of that technology. Let them make the market.”

This is the power of the fast follower. You let your competitor spend the money and take the initial risks. You come into a market that’s already been warmed up, armed with several advantages:

More agile tech: You’re not saddled with the legacy systems the first mover had to build. You can leverage the latest, most efficient best practices from day one.

A clearer target: You can analyse the leader’s product, identify its gaps, and build a better, more refined solution. You innovate on the margins they ignored.

Capital efficiency: Your marketing dollars go further because you’re not creating demand from scratch; you’re capturing it.

This isn’t about being the “tail,” as Adia puts it. It’s about being the “neck”—essential, powerful, and strategically positioned. Google followed Yahoo. Netflix, once a challenger, offered itself to Blockbuster, who famously said no. The history of tech is filled with number twos who eventually took the crown, not by being first, but by being better.

Innovation beyond the obvious

So if you’re not outspending the leader on flashy Super Bowl ads, how do you win? Adia’s answer is to innovate in places others overlook—specifically, in distribution.

Marketing in a market like Nigeria is incredibly difficult and expensive. There are no consolidated channels to reach the whole country. A national campaign is a logistical nightmare. But distribution, she notes, can be a more direct and powerful lever.

She points to the brilliant, scrappy strategy of Biggie Cola against the goliath, Coca-Cola. While Coke was sponsoring global events, Biggie was focused on one thing: being everywhere. They innovated on the ground, ensuring their product was in every neighbourhood kiosk, closer to the customer’s point of need.

This isn’t just for physical products. Adia shared an incredible story from her time at Etisalat, where they ran an exercise to calculate the average distance between every single person in Nigeria and the nearest Etisalat retail outlet. They then tracked how often those outlets ran out of stock. That’s not marketing; that’s a scientific approach to presence. It’s a recognition that the best product in the world is useless if the customer can’t get it when they need it.

This mindset—of finding your unique advantage and doubling down—doesn’t just apply to building billion-dollar companies. It’s a powerful framework for building a career.

The $10k task

As our conversation unfolded, I realised that Adia applies the same rigorous strategic thinking to her own life. When I asked her what she optimises for, her answer was telling.

“Earlier in my career, I optimised for money and interest,” she said. “But now, I optimise for interest.”

This shift is the personal equivalent of choosing to be a strategic number two. It’s about declining opportunities, even lucrative ones, that fall outside your “zone of genius.” It’s about knowing which battles to fight and which to cede.

She introduced a framework that’s been stuck in my mind ever since: the “$10K Task,” created by American productivity expert Khe Hy.

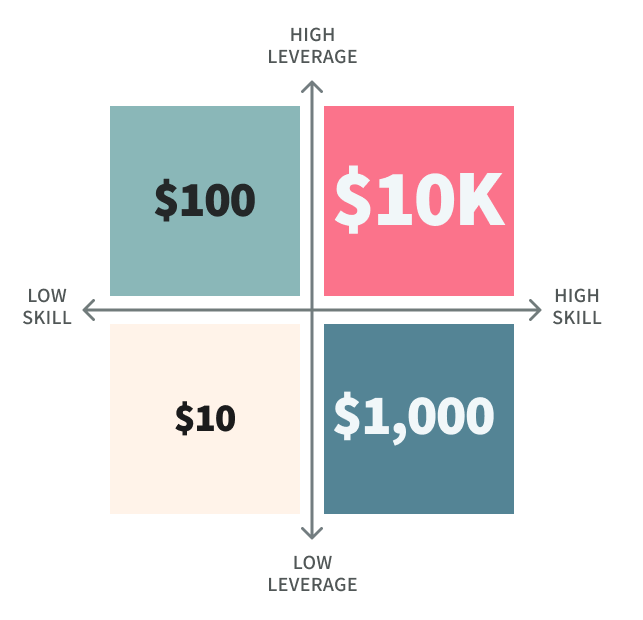

Here’s the thinking behind the framework. Not all tasks are created equal. Some consume hours but add little value, while others can transform a business.

At the base are $10 tasks like scheduling meetings or formatting documents—necessary but low-impact. $100 tasks involve standard execution, such as drafting reports or managing campaigns. $1,000 tasks raise the stakes with high-skill actions like closing a client deal or launching a marketing experiment.

But the real game-changers are $10,000 tasks. These are high-leverage activities that produce ripple effects long after completion: designing a scalable growth model, securing a strategic partnership, or shaping a narrative that positions a company as a market leader. They cannot easily be delegated and demand vision, judgment, and leadership.

For Adia, years ago, speaking on panels was a “$10k task” for her—it helped her find her voice and build her profile. Today, it’s a “$1k task.” The challenge is gone. So what’s her new “$10k task”?

“Teaching people who wonder or want to do it, how I started or how to find their own voice.”

Her focus has shifted from doing to empowering. It’s a beautiful evolution, a recognition that true mastery lies not just in honing your own skills, but in scaling your impact through others. This is how you build a legacy.

This whole philosophy is wrapped in a refreshing humility. Adia describes her career not as a master plan executed to perfection, but as a “backward-looking experience.” It’s only in retrospect that the dots connect into a coherent sentence: “designs, builds, and scales tech ventures.” It’s a liberating thought, freeing us from the pressure of having it all figured out. The key is to simply optimise for interest, focus on your “10k” tasks today, and trust that the story will write itself.

This is just a fraction of the wisdom Adia shared. In our full conversation, we dive deeper into making metrics truly actionable (and creating a “soft life” for managers), her perspectives on AI and the no-code movement, and her deeply personal definition of success, rooted in peace and gratitude.

📺 Watch the full conversation with Adia Soho here:

It’s great to be back

Note

Back at Condia, I launched the Quest podcast with the same name as this newsletter—mainly because no better name came to mind at the time. That was long before I even thought about leaving.

While the podcast technically belongs to Condia, I realised the pilot episodes could be the perfect way to kick things off here.